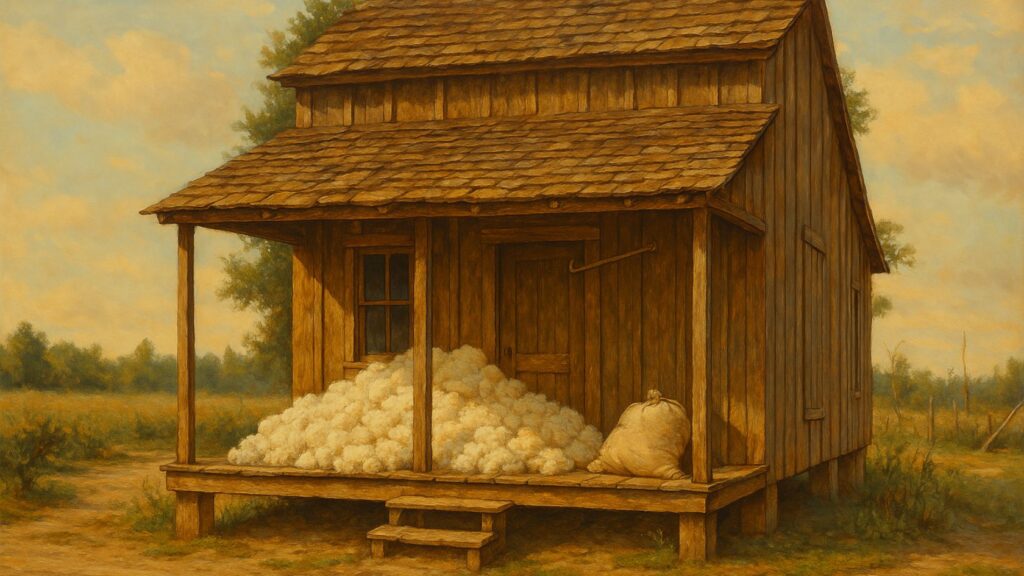

A simple tenant house. A neat porch stacked high with raw cotton. The image is reimagined from a 1935 photograph taken on the grounds of Maria Plantation in Arkansas. Quiet as it appears, this scene reflects a system that was anything but gentle.

A simple tenant house. A neat porch stacked high with raw cotton. The image is reimagined from a 1935 photograph taken on the grounds of Maria Plantation in Arkansas. Quiet as it appears, this scene reflects a system that was anything but gentle.

This wasn’t the plantation house. It was one of the many structures where tenant farmers lived and worked—on land they didn’t own, growing cotton they couldn’t profit from. The labor was grueling. The compensation insultingly low. At times, workers earned as little as five cents an hour, barely enough to feed a family, let alone rise out of debt.

Captured by Farm Security Administration photographer Ben Shahn, the original images were part of a national effort to document rural poverty during the Great Depression. They reveal lives shaped by exploitation, not accident. Cotton on the porch wasn’t just a crop—it was a symbol of who held power, and who bore its cost.

Maria Plantation sat somewhere in Arkansas, in the Mississippi Delta region, where cotton dictated the economy and the lives within it. Tenant farmers, often Black and impoverished, had little choice but to endure a cycle of dependence. Even when mechanization arrived and changed the nature of agriculture, the same families were cast aside—without protection, acknowledgment, or land of their own.

The echoes of that era still linger. Rural communities today face different tools, but the same machinery: land consolidation, vanishing autonomy, and systems designed to prioritize profit over people.

The image may look calm, even nostalgic. But there’s a weight in that cotton, and a truth that shouldn’t be softened. What stood on that porch was the product of lives laboring under quiet coercion—structured, sanctioned, and sustained by policy and power.

Do tenant farms still exist?

Here’s the current reality, plain and direct:

- Rented farmland is widespread: As of the most recent USDA data, about 40% of U.S. farmland is rented, and much of it is worked by people who do not own the land. These farmers range from full-scale operators leasing thousands of acres to small family farmers barely breaking even.

- Land concentration is accelerating: Ownership is increasingly in the hands of corporations, absentee landlords, and investment groups. Many rural families who once owned land now lease it back just to stay afloat.

- The economic leverage is the same: Like in the sharecropping era, tenant farmers today often face tight margins, heavy debt, and little control over prices, terms, or weather-related risks. They provide the labor and bear the risk, but profits usually flow upward.

- No feudal cabins, but the hierarchy remains: Today’s tenant might drive a modern tractor instead of a mule, but the power imbalance hasn’t gone anywhere. It’s just been digitized, financed, and wrapped in legal contracts.

So yes—tenant farming persists. It’s not romantic, and it’s not gone. It’s simply evolved into a more bureaucratic and corporate-friendly form of the same old imbalance.

The Past, Reimagined Like Rockwell #8

Is this the “Again?” #2